Sierra Leone's National Primary School Examination (NPSE) results published last week saw Rising students register some of the strongest results in the country.

Rising students achieved an average aggregate score of 303.5, the fifth highest average score out of the 4,635 schools in the country, according to the official report from the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education (MBSSE).

57 Rising students sat the exam from Rising's four campuses and all passed. The total number of passes is higher than any other school in the top 10.

This 100% pass rate for Rising compares to 81.2% nationwide and 88.2% for other private schools, while Rising’s average aggregate score of 303.5 compares to a national average of 249.1 for all students and 264.0 for private school students.

Results were extremely consistent across Rising's four primary school campuses. If they were treated as separate schools rather than a single entity, they would fill 4 of the top 9 places in the school rankings.

We were also delighted to see continued evidence of gender equity. At Rising, girls out performed boys (average score of 304.0 vs 302.8 for boys), whereas nationally they did slightly worse than boys (248.7 vs 249.6)

Of course, our own Rising Academy Network of schools is only one part of what we do in Sierra Leone. We're also looking forward to seeing how the 25 schools we've been supporting through the government's Education Innovation Challenge programme have fared, as well as the more than 500 schools we're working with under our partnership with Freetown City Council and EducAid.

But for now, huge congratulations to the students for making us so proud, and thanks to our parents, teachers, school leaders and support staff for their hard work in supporting this achievement.

Growing our partnerships with government

On the subject of government partnerships, I'm delighted to announce that in the next academic year Rising will be adding a new partnership in Sierra Leone, innovating within two of our existing partnerships in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and entering into a partnership with the Government of Ghana for the first time. Taken together, these programmes will see us working in more than 800 schools with a quarter of a million students in the coming year.

In Sierra Leone, we've been chosen as one of the operators for a new Education Outcomes Fund programme that will see us working with 66 schools in the north and east of the country. We're also deepening our Freetown City Council partnership, implementing and evaluating our catch-up numeracy programme FasterMath in a subset of the schools.

In Ghana, we're joining forces with pioneering NGO School for Life Ghana to support out-of-school children and improve the quality of 170 of the country's most disadvantaged schools under another Education Outcomes Fund programme.

In Liberia, our longstanding partnership with the Government of Liberia under the LEAP programme looks set to be renewed for another 5 years. In addition to our existing support to 95 government schools through curriculum, teacher coaching and school data systems, we'll be working with Imagine Worldwide to explore the potential for blended learning via adaptive software on tablets to improve outcomes for students.

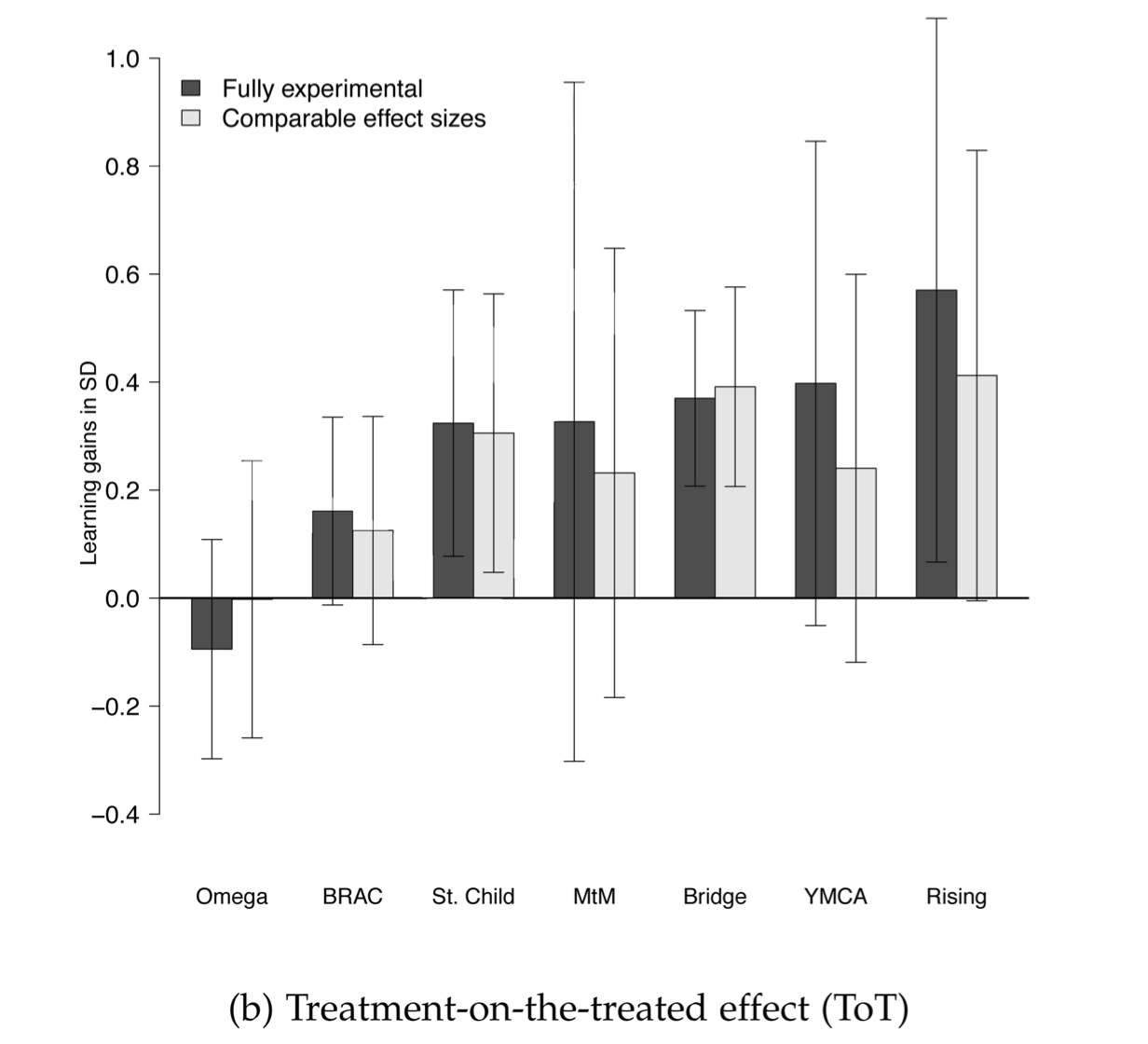

Rigour, experimentation and evidence are fundamental to our approach to these partnerships. We’re currently participating in three "gold standard" randomised controlled trials in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and three more will be starting in Sierra Leone and Ghana soon. For us, this is how we demonstrate to our government partners the impact we are having, identify what we need to improve and fine tune, and advance the global public good of an improved evidence base about what works.

Other news from around Rising

We're coming to the end of the second term at RISE, the new school we launched in Ghana back in January (and our first in Ghana under the Rising banner). The initial feedback from parents and students has been really positive and we're excited to roll out further RISE campuses in the years ahead.

Shabnam Aggarwal has joined Rising as our first Chief Technology Officer to lead our rapidly growing content and digital division. Shabnam has extensive experience of building, managing and shipping tech products, having formerly founded KleverKid, a venture backed edtech startup in India, and most recently as entrepreneur-in-residence at Dimagi, where she led their innovation lab.

One of her early priorities will be the continued development of Rori, our virtual math tutor chatbot, which has been shortlisted for another major award - we hope to hear if we've been successful in September.

Thanks as ever for all your support. Don’t hesitate to drop me a line on email or follow us on social media.